Road to Reconciliation

As the country began to move past war and political instability, Cambodians initiated many efforts to promote peace and reconciliation in their communities. This exhibition room highlights the “Dhammayietra Peace Walks” and the resilience & dedication of Cambodian peacebuilders.

The suffering of Cambodia has been deep.

From this suffering comes great compassion.

Great compassion makes a peaceful heart.

A peaceful heart makes a peaceful person.

A peaceful person makes a peaceful family.

A peaceful family makes a peaceful community.

A peaceful community makes a peaceful nation.

And a peaceful nation makes a peaceful world.

May all beings live in happiness and peace.

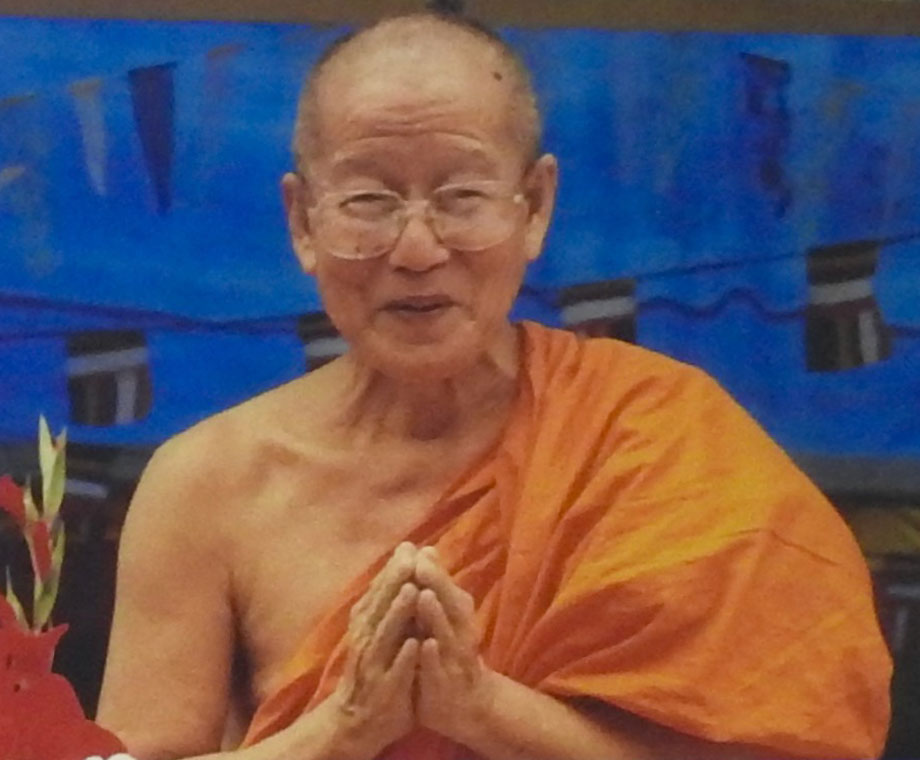

Samdech Preah Maha Ghosananda’s Prayer

Dhammayietra Peace Walks

Conceived in 1992 as a one-time event to help Cambodians move past fear and begin the reconciliation process after two decades of war, the Dhammayietra sought to teach peace by example, with its route passing through many of the country’s politically unstable, war-torn and landmine-ridden regions to promote peace.

The first walk took place in 1992 as the refugee camps on the Thai border were preparing to close with the planned repatriation of some 350,000 Cambodians.

Over 100 Cambodian refugees, joined by Maha Ghosananda and representatives from various international faith groups, monks, nuns and hundreds of local supporters, left the refugee camps on the Thai border to travel 450 km through parts of Cambodia that continued to see outbreaks of conflict between guerrilla groups and government troops. By the time the walkers reached Phnom Penh, their number had swollen to more than 1,000.

Following Maha Ghosanda’s call that “We must walk where the troubles are”, each year the walkers carried messages of hope and peace through areas of the country that had known nothing but war.

About Maha Ghosananda

Samdech Preah Maha Ghosananda, founder of Dhammayietra Peace Walks, dedicated his life to spreading messages of peace, compassion and loving kindness. Maha contributed greatly to the rebirth and restoration of Buddhism in Cambodia. He built hundreds of Buddhist temples inside the refugee camps along the Thai-Cambodia border so people could pray and practice their religion.

Resilience:

Celebrating the Lives of Cambodian Peacebuilders

A series of stories celebrating the lives and achievements of some of Cambodia’s most prominent peacebuilders.

For Vannath, neither her extensive activism for democracy nor her leadership in Cambodian civil society was part of any plan.

Growing up in a devout Buddhist family, she was taught early on that change is the only certainty. She did not dream of her future and says simply, “dreaming and planning is not my type…I choose day by day.”

Vannath has spent almost 20 years helping to reconstruct and rehabilitate her war-torn country. As president of the Coalition for Free and Fair Elections in the early 90s, she monitored election processes in order to improve transparency.

Then, as president of Cambodian Social Development from 1996-2006, she helped establish the first series of public forum debates on national issues, as well as the first national survey on corruption and the first national curriculum on transparency and accountability.

As a testament to her dedication, she was one of 1,000 women nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 2005.

Although her accomplishments speak to her focus and ability, Vannath remembers her struggle to become the activist she is known as today. She recalls, “When I arrived in the [refugee] camps, they [fellow refugees] looked at me like I was their savior.”

She explains that because she was one of few surviving members of the educated class, they expected her to be a leader. But being a leader was not her disposition. In her time, Cambodian women were not vocal. They were not involved in the greater community, and neither was she.

When asked what made her decide to become an activist, she says, “my awakening was seeing Khmer wander from the tombs like living ghosts…” Her experiences with suffering were her motivation. “Although it went against my culture, I decided to be involved.”

For the future generation, Vannath reminds them that life is a struggle for balance. Each person balances between physical and mental growth, family and work.

“Cambodia must balance between national growth and the dignity of the people.” She explains, “I am not so naïve as to think I can change the country, but I continue fighting for the struggle.”

As long as the struggle exists, she believes the freedom to make change is possible. In her dedication, Vannath strives to ensure that young leaders have the freedom of choice to build a balanced future.

Sokha was eager to share his journal. In it was an assortment of quotes that he has been collecting for over 20 years. He said that he doesn’t recall specific teachers who showed him how to be a leader or what to value in life, but that words from various books, politicians, and scholars are his guide. When he was younger, he loved reading novels about protagonists who were “brave” and “fought for the people.” They became his role models.

“Who wanted to live in the jungle hungry, mosquito-bitten, and with no shelter from the rain and wind? No one. If the man quitted, he would be accused of betrayal then killed. If he ran away, the army would catch and kill him. They were only motivated by their stomachs. I am not angry with the soldiers. They were victims, too.”

In 1989 at the age of 18, Sokha ventured from his home province of Takeo to get a higher education in Phnom Penh. He explained that the most difficult part was arriving in Phnom Penh at midnight, a poor farmer’s son who knew nobody and had no place to sleep. Five years later, he left the capital with a bachelor’s degree in Psychology and Pedagogy from the Royal University of Phnom Penh and began his career as a teacher.

Sokha is currently the Executive Director of the Youth Resource Development Program, a well-established, local NGO that offers free courses to university students to develop critical thinking skills and social responsibility. He strongly believes that receiving an education means receiving not a certificate, but rather the tools and ability to respond to changing situations. Today Cambodia is undergoing change unlike any in its history. Sokha is determined to arm the next generation with the intelligence and conscience to create a peaceful future.

“There are no limitations to the mind except for those we acknowledge.” – Napoleon Hill.

By 1970, Thavory could not remember how many times she had taken refuge in trenches to escape the American bombs. She turned 15 that year and the Khmer Rouge revolution had just reached her village in Kampong Thom.

They recruited her and other village youth to help further the movement: “At night I travelled to give speeches at surrounding villages. I spoke about the injustice of the carpet bombing, about the capitalists taking all the money while the farmers did the work, and how we should rise against Lol Nol and the capitalist suppressors.”

Thavory became disenchanted with the movement when the Khmer Rouge mobilisation began – when child soldiers were sent to the front lines of the fighting and her 16-year-old younger brother, a Khmer Rouge soldier, died of malaria.

She had lived in Phnom Penh for only one year before the KR overran the capitol.

Thavory was evacuated with the rest of the population and sent to work in the mobile youth units digging irrigation dams, “Working under the hot sun led to skin diseases. Sometimes I thought I would rather die than suffer through the [incessant] itching.”

When the country came under Vietnamese control, she explained how violence echoed throughout communities, “Some students carried guns to schools to show off their family status. Men would fight over traffic accidents. No one felt safe.”

Hout Thavory said her experiences led her to join the Working Group for Weapons Reduction in 2001. With them, she helped write a national curriculum on peace and disarmament and travelled across the country to train teachers on weapons law and methods to teach young people about the dangers of small arms. This work also led her to countries such as Peru, Albania, and Germany to share her experiences with her transition from war to post-war.

Today, Thavory is the executive director of Khmer Ahimsa, a non-governmental organization advocating non-violent resolutions to local conflicts. Through conducting workshops on issues ranging from domestic violence to land advocacy, Thavory hopes this type of education might undo the tendencies towards violence that she has long witnessed.

If given the opportunity to advise the young generation, Thavory says, “Life is a cycle. If today is hard, tomorrow will be easy, and if today is easy, tomorrow will be hard. You must be patient because everything impermanent. Things can always change.”

“All news stopped coming out of Cambodia when the border was sealed toward the end of May [1975],” Thida recalled of her experience living in Thailand while Cambodia fell to communism. “I lost contact with my family two months before that and had no idea of the cruelty they were living through.”

In 1979, Thida began working for the refugee service in the American Embassy in Bangkok, Thailand, hoping to find her family. She dedicated her efforts to convincing the Thai government to end the forceful return of Cambodian refugees back into Cambodia. By distributing the names of refugees with family in other countries, her team worked to convince embassies to acknowledge the magnitude of the issue and take action.

“I remember seeing my family among the other refugees. I was shocked that there was no difference between them and other people – all had big stomachs, dirty clothes, red hair from malnourishment, and were very skinny. In that camp, I realised that we are all human, we are the same…the other refugees became my extended family.”

Thida explained that she used to think people were poor because they were lazy, but the sameness that she saw taught her that there are things much greater than a person’s work ethic that determine their situation in life.

After her return to Cambodia in 1992, Thida initiated a volunteer programme to address the severe lack of human resources for Cambodia’s reconstruction. She brought Cambodian American volunteers to teach skills for rebuilding the country’s institutions; they helped manage civil society groups, develop curriculum for the university, and organise government ministries. In the 1990s, she advocated for non-violent action, serving as advisor to Ponleu Khmer to oversee the celebrated Dhammayietra (nationwide peace marches), and in 1998 as the national coordinator for the Methathor coalition, she mobilised support for peaceful elections.

Currently she is the founder and executive director of SILIKA, a non-governmental organisation that continues the capacity building work she began from the start.

When asked why she chose to pursue this type of work, Thida explained that she did not live through the labour camps, but that she has lived and is living through its consequences. “Whether or not I was involved, the decision of policy makers affected my life. I was not exempt…”

Today her work is more than a job. It is a way to determine her own future. To the younger generation, Thida advises them to be reflective, to not be afraid of questioning and changing their assumptions. She says that it is important they consider their own perspective – it is a necessary part of understanding their situation in life and making dreams for the future.

Sokeo said that in many ways, it would have been easier to live inside the Cham community than outside it, “With other Cham I feel safe to share my thoughts. I can talk about my future, our community, our religion, and I do not feel threatened…outside it was different.”

He explained that Cham Muslims, an ethnic and religious minority in Cambodia, live in peaceful communities and usually do not venture outside them to do business or get more schooling, often times because they face discrimination for their religious practices. Sokeo’s initial motivation to leave home was to get educated for an “easy” job, one that didn’t require hard labor. What he found in the city though, was a love for different perspectives and cultures – an experience he wanted to share with others.

Sokeo works to integrate Cham communities and individuals into the greater Cambodia, “We want to live in harmony. If we live separately, without good relationships with others, there will be conflict because of misunderstandings. It might be difficult for people meeting the first time to talk or share their perspectives, but they have to work through that. It gets easier.”

As the executive director for the Alliance for Conflict Transformation (ACT), Sokeo hopes to improve cooperation between civil leaders across religious, ethnic, and geographical divides. The Alliance for Conflict Transformation, a non-governmental organization established in 2002 to help facilitate sustained country development, focuses on building cooperative skills in civil leaders. In his ten years with ACT, Sokeo has been key to the programs’ expansion, overseeing its outreach to several of Cambodia’s provinces and maintaining its partnerships with the Ministry of Education and other institutions. He initiated the Inter-Ethnic Peacebuilding Project (IEPB) as a way to build respect and cultural awareness in civil society leaders.

Because of his own experiences with ethnic and religious discrimination, he sees ACT as a “place where I can heal myself and do something for others, not only for my own community but also for other groups who suffer from discrimination.” When asked what he has learned from working with people of different faiths and backgrounds, Sokeo says, “Having to work closely with others, I think about showing respect differently. I use the Buddhist way of greeting when I greet Buddhists – some say a Muslim should not do this, but I see it as a way of showing respect.” By practicing respect and open-mindedness, Sokeo sets an example for all Cambodians, young and old alike.

Kassie pointed out the irony in how speaking English had been both a curse and a gift in his lifetime.

On one hand, it was the reason he was suspected of being CIA and tortured for confession during the Khmer Rouge era. On the other, it is the language he’s used to broadcast his story, traveling across the world to educate audiences about humanity and hope. Kassie is the founder of the Cambodian Institute of Human Rights, a civil organization that has reached out to several provinces with workshops on human rights and made strides to include human rights education in the public school system. Kassie is also an advocate of good governance and democracy. Between 1997 and 2002 he was the vice chairman of the national election committee advocating fair elections and in 2004, a secretary state of justice. In 2006 he resigned from political life and returned to teaching English.

Kassie finds a passion for teaching, for interacting with young Cambodians in a way that prepares them for the future. He gets joy from seeing the students’ progress, “First they understand three or four words, then three or four sentences. Then they make their own sentences!…They learn English from me, and maybe they will go study more abroad. And then they might bring Cambodia up to speed with the rest of the world.”

Kassie is one of few survivors of the Khmer Rouge interrogation system. When asked what was the most important lesson he walked away with, he answered, “Never lose hope. I never lost hope for survival. Hope kept my brain working…I was able to see opportunities, be creative, and find ways to help myself.” He recalled past times when he had managed to obtain tobacco to trade for traditional medicine, or when he persuaded his 14-year-old jailors to leave him leftover coconuts. From such experiences, he strongly believes that hope lead him to creativity while creativity led him to courage and initiative.

To young Cambodians, he explains that soon, the level of knowledge in the world will be much higher than it is today. “It is not enough for students today to be satisfied with knowing as much as their teachers. They need know beyond what their teachers know.” When asked about where he saw Cambodia in the future, Kassie says “Cambodia has many resources: mountains for dikes, rivers for hydroelectricity, and much more.” He admits that there is little left his generation can do and so looks to young Cambodians to use their energy and time to educate themselves and their country. “The level of knowledge is always rising,” he says. “You have to orient yourself towards the future and aim high.

She knew she was different from the other children. She could not play like they played, and she did not look the same – she used her hands to help move through the house. “The most difficult part is feeling shy,” she explained, “I don’t want people to look at me and see only my missing leg…I am more than that. I am the same as you.”

Kosal was born in 1984, the fourth of six children in a rice farming family. When she was five, she was injured by a landmine while helping her mother in the rice fields. Her leg was amputated too high to allow her to use a prosthetic, and today she walks with a crutch.

Years after the incident, a staff member of the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) noticed her at a Battambang clinic. In 1995, at the age of 12, Kosal joined ICBL as a representative of landmine victims around the world.

“I can speak. I can be an example. I have to do something while I have the chance to.”

ICBL is dedicated to eradicating the production and use of antipersonnel landmines. With the organization, Kosal has travelled across the continents to tell her story, gathering thousands of signatures to support the ban. The culmination of her and ICBL’s campaigning efforts came in 1997, when 122 countries signed the mine ban treaty agreeing to prohibit the use, stockpiling, production, and transfer of anti-personnel land mines.

Today, Kosal works full time as the ICBL youth ambassador, spreading awareness in order to help countries fund mine-clearance, improve victims’ assistance, and strengthen international cooperation. “Everyone is crying and smiling,” she said, describing a seminar attended by landmine victims.

“They are crying because they are poor and their disability makes earning a living in the rice-farming villages very difficult. They are smiling because although they are strangers, they feel safe from judgment [at the seminar] and able to share their feelings.” Kosal explained that many live in communities that assume people with disabilities are incapable of work: “many feel ashamed,” she said. In response, Kosal advocates for the basic rights of disabled people, such as the right to accessible education and to be involved in the community.

Through her work and that of IBCL’s vocational training program, many more are able to transcend the stigma. For future generations, Kosal hopes that no more children will be labeled “mi-kombak”, no more be taught that they are defined by their limitations, but rather that they, like anyone else, have limitless possibilities.

*mi-kombak – a derogatory term for someone who is physically handicapped

“In 2001, the former Khmer Rouge still dressed like Khmer Rouge. They didn’t wear black anymore, but they wore shoes made from tires, carried things in backpack, and the girls kept their hair short. They did not talk to ordinary villagers because they believed those who were not like them were bad people – capitalists with the government.”

That year, Varine was sent to Udor Mean Chey, a Khmer Rouge reconciliation zone where former Khmer Rouge had difficulty re-integrating with the village people. As an educator with the Cambodian Development Resource Institute’s (CDRI) social development program, she went to help facilitate reconciliation.

She arranged a meeting where villagers and former Khmer Rouge shared their thoughts and feelings: “At first the man [former Khmer Rouge] did not talk. But after hearing villagers speak about their fears and suffering when the Khmer Rouge were in power, he shared his own. He talked about how strongly he missed his wife and son when he was sent far away to fight.” These meetings allowed the communities to come together and focus on their similarities rather than their differences. “I wanted them to understand each other,” she said. According to Varine, listening to each other’s suffering showed the villagers and former Khmer Rouge their common humanity, a place to begin building trust and reconciliation.

Varine has worked as an educator with CDRI for the past ten years because, “We’ve [Cambodians] seen war before, and we don’t want to meet it again.” Using case studies identified by CDRI’s research as significant issues affecting Cambodia, she teaches target groups skills to identify conflict, analyse its causes, and create strategies for its prevention and resolution. Topics range from water distribution to domestic violence and participating groups include commune officials, journalists, police, and more. By teaching participants to be critical of their own assumptions or to consider other people’s motivations, she hopes to build their capacity for non-violent problem solving.

Varine works with individuals, and sometimes she feels the work “is small and may not make a big difference”, but she reminds herself that change on an individual level has an important role to play. “The actions of a person can become the actions of a group.” Varine believes that in order to build a country that can resolve its problems without resorting to force, a good place to start is with the perceptions and abilities of ordinary people.

When asked why an education was important to him, Virak said, “It’s valuable because you can use it to make a living; you can sell your expertise or employ yourself…once you have an education, no one can take it from you.”

Virak is the executive director of the Cambodian Legal Education Center (CLEC), a local NGO that provides legal information to the Cambodian public. His dedication to building a more democratic Cambodia stems from his experiences as a young man living in the country during and after war. Virak recalls policies that had severe consequences for ordinary citizens who had no part in making them. He remembers arbitrary arrests, extra judicial killings, and a deep-seated fear of the police that led to mass intimidation and vulnerability.

Virak adds, “The more injustice people feel, the more they’re forced to look to violence to solve the problem…This is what I saw and that’s why I told myself we [Cambodians] need to do something.”

Before the war, when he was in high school, Virak would visit the Royal University of Phnom Penh and imagine himself a university student. When the KR came to power in 1975, his dream was cut short. He survived the heavy labor, and when the Vietnamese came, he made his way to the capital. There he found the education and experience that led him to become the activist he is today.

As director of CLEC, Virak oversees the organization’s activities: promoting legal education, empowerment, and advocacy to target groups like union leaders, management, and citizens negatively affected by land concession practices. His commitment to Cambodia is also expressed by his role in civil society; as a civilian leader, Virak is known for his human rights advocacy. In 2005, he was jailed for his connection to banners that displayed criticisms of the Cambodian government. If not for the international protest that resulted from his arrest, Virak may have spent much longer in Prey Sar prison.

He was released after eleven days, and in 2006, due in part to his advocacy and public pressure, Cambodia’s UNTAC law concerning criminal defamation was rewritten to exclude imprisonment as a lawful punishment. Virak hopes his work helps establish a foundation of active citizenship for young people. He looks to build their capacity as civilians because he believes that for young people to determine the future, they have to be a part of the decisions that shape it.

In memory of running across provinces to escape American carpet bombs, his parents named him Khet. Khet was too young to remember the Khmer Rouge times, but he grew up in its echoes. He recalled clearly his childhood in post-war Cambodia, where many children were orphans, violence was merely a way to get things done, and there was an immense sense of hopelessness.

It was not until he studied at university that he began to better understand his life in connection to the country’s situation, “I talked with friends about the history we learned in class and the country’s situation…and how we who have an education can help…We were creating hope for ourselves [where before there wasn’t any].”

Khet is one of four founders of Youth For Peace (YFP), a non- governmental organization established in 2001 to help Khmer students develop critical thinking skills.

He explained that many individuals who survived Cambodia’s time of war passed the survival skills they learned to their children.

He suggested behaviours like avoiding attention, following the leader, and not making long-term goals are part of the survival mindset that he sees continuing in the young generation, “They [survivors] teach their children how to survive in a repressive society…pretending to not hear or see anything, that’s part of the way they think, and it’s what they pass on. That’s why we have to work with young people to give them some sort of option, some way of critical thinking and self-expression to create a culture of democracy.”

For the past ten years, he has helped provide a safe space for youth to not only identify and discuss issues in society, but also recognise their responsibility to be a part of the solution.

Young Leaders for Peace, one of several programs under YFP’s direction, teaches community needs assessment and budget planning to prepare students for community development work. Apart from its courses, YFP accommodates a student centre, a library, and a supportive staff to operate workshops in Phnom Penh, surrounding communities, and other provinces.